Utopies de la libération : Houria Bouteldja à propos du féminisme, de l’antisémitisme, et des politiques de décolonisation

De Ben Ratskoff

Le 5 avril 2018

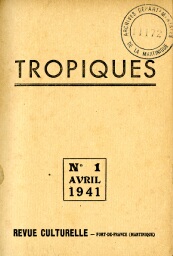

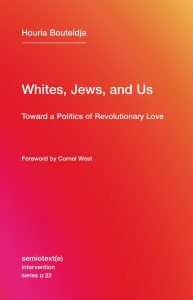

En mai 1943, l’écrivaine surréaliste noire et militante Suzanne Césaire a demandé des rations de papier au gouvernement de Vichy, en temps de guerre, administrant la Martinique. Elle avait besoin de ce papier pour imprimer le prochain numéro de Tropiques, un journal consacré à l’intersection du Surréalisme et des politiques anticolonialistes dans les Caraïbes. Le gouvernement a refusé sa demande. Dans une vertigineuse démonstration de double discours, les collaborateurs du régime Nazi ont affirmé que le journal de Césaire était trop raciste et sectaire, dans son engagement assumé pour la négritude, et dans sa révolte littéraire contre la civilisation française. Il est à la fois troublant et éclairant de trouver un discours quasi-identique entourant la publication récente d’Houria Bouteldja, Les blancs, les juifs et nous : vers une politique de l’amour révolutionnaire. A la sortie du livre en France en 2016, un véritable lynchage s’est produit dans les médias. La pensée unique des intellectuels Français, de droite comme de gauche, s’est précipitée pour discipliner cette femme Arabe qui avait osé démystifier le conte de fée que la France se raconte à elle-même. De bien laids qualificatifs lui ont été attribués : Bouteldja était donc une raciste antiraciste ! Une néo-nazie ! Une homophobe ! Pas grand-chose n’a changé depuis la requête de Césaire pour les rations de papier en Martinique.

En mai 1943, l’écrivaine surréaliste noire et militante Suzanne Césaire a demandé des rations de papier au gouvernement de Vichy, en temps de guerre, administrant la Martinique. Elle avait besoin de ce papier pour imprimer le prochain numéro de Tropiques, un journal consacré à l’intersection du Surréalisme et des politiques anticolonialistes dans les Caraïbes. Le gouvernement a refusé sa demande. Dans une vertigineuse démonstration de double discours, les collaborateurs du régime Nazi ont affirmé que le journal de Césaire était trop raciste et sectaire, dans son engagement assumé pour la négritude, et dans sa révolte littéraire contre la civilisation française. Il est à la fois troublant et éclairant de trouver un discours quasi-identique entourant la publication récente d’Houria Bouteldja, Les blancs, les juifs et nous : vers une politique de l’amour révolutionnaire. A la sortie du livre en France en 2016, un véritable lynchage s’est produit dans les médias. La pensée unique des intellectuels Français, de droite comme de gauche, s’est précipitée pour discipliner cette femme Arabe qui avait osé démystifier le conte de fée que la France se raconte à elle-même. De bien laids qualificatifs lui ont été attribués : Bouteldja était donc une raciste antiraciste ! Une néo-nazie ! Une homophobe ! Pas grand-chose n’a changé depuis la requête de Césaire pour les rations de papier en Martinique.

La réception du court manifeste de Bouteldja s’inscrit dans la continuité de la polémique surréaliste de Césaire, et, de manière plus évidente encore, de la polémique autour de l’ouvrage révolutionnaire de son mari Aimé Césaire, Discours sur le colonialisme (1950). Traduit en anglais, de manière artistique et délicate par Rachel Valinsky, Les blancs, les juifs et nous est un manifeste passionnant et poétique qui vise la métropole impériale et son mythe de l’innocence. Le livre est traversé d’un optimisme saisissant, formulant un magnifique appel à un mouvement décolonial métropolitain, pensé comme une force politique de libération. Bouteldja s’attaque ainsi au problème de l’Eurocentrisme, de l’impérialisme, de la mondialisation, et propose l’expérimentation d’une organisation politique qui, selon les mots de son camarade Sadri Khiari, a pour projet de « penser l’unité et la division ensemble et d’accepter la convergence et l’antagonisme comme des chemins paradoxaux vers la libération ». Le premier chapitre identifie une contradiction, qui conditionne l’adresse de ce livre aux blancs, aux juifs et aux personnes indigènes : le sionisme non repenti de Jean-Paul Sartre. D’un côté, Sartre défend le militantisme anticolonial en Algérie et dans le Moyen Orient ; d’un autre côté, il soutient la création d’un état-nation Juif en Palestine. Bouteldja affirme que l’engagement simultané de Sartre pour l’anticolonialisme et pour le sionisme est dû, essentiellement, à sa blanchité. La blanchité, en somme, était un marqueur de ses limites politiques. Dans un passage provoquant, Bouteldja écrit : « Celui qui a déclaré: « C’est l’antisémite qui fait le Juif » a par la suite prolongé le projet antisémite sous sa forme sioniste et a participé à la construction de la plus grande prison pour les Juifs. Dans la précipitation pour enterrer Auschwitz, et pour sauver l’âme de l’homme blanc, il a creusé la tombe du juif. » En d’autres termes, Sartre a perçu l’antisémitisme comme un mécanisme européen d’exclusion, mais a en même temps participé à ce mécanisme en excluant le futur des juifs en dehors de l’Europe, à la faveur d’un Etat-nation séparé. Pour Bouteldja, le sionisme de Sartre est le symbole à la fois du refus de la gauche blanche d’abandonner l’État-nation, mais aussi de la récupération obstinée de l’idée d’une innocence européenne.

La réception du court manifeste de Bouteldja s’inscrit dans la continuité de la polémique surréaliste de Césaire, et, de manière plus évidente encore, de la polémique autour de l’ouvrage révolutionnaire de son mari Aimé Césaire, Discours sur le colonialisme (1950). Traduit en anglais, de manière artistique et délicate par Rachel Valinsky, Les blancs, les juifs et nous est un manifeste passionnant et poétique qui vise la métropole impériale et son mythe de l’innocence. Le livre est traversé d’un optimisme saisissant, formulant un magnifique appel à un mouvement décolonial métropolitain, pensé comme une force politique de libération. Bouteldja s’attaque ainsi au problème de l’Eurocentrisme, de l’impérialisme, de la mondialisation, et propose l’expérimentation d’une organisation politique qui, selon les mots de son camarade Sadri Khiari, a pour projet de « penser l’unité et la division ensemble et d’accepter la convergence et l’antagonisme comme des chemins paradoxaux vers la libération ». Le premier chapitre identifie une contradiction, qui conditionne l’adresse de ce livre aux blancs, aux juifs et aux personnes indigènes : le sionisme non repenti de Jean-Paul Sartre. D’un côté, Sartre défend le militantisme anticolonial en Algérie et dans le Moyen Orient ; d’un autre côté, il soutient la création d’un état-nation Juif en Palestine. Bouteldja affirme que l’engagement simultané de Sartre pour l’anticolonialisme et pour le sionisme est dû, essentiellement, à sa blanchité. La blanchité, en somme, était un marqueur de ses limites politiques. Dans un passage provoquant, Bouteldja écrit : « Celui qui a déclaré: « C’est l’antisémite qui fait le Juif » a par la suite prolongé le projet antisémite sous sa forme sioniste et a participé à la construction de la plus grande prison pour les Juifs. Dans la précipitation pour enterrer Auschwitz, et pour sauver l’âme de l’homme blanc, il a creusé la tombe du juif. » En d’autres termes, Sartre a perçu l’antisémitisme comme un mécanisme européen d’exclusion, mais a en même temps participé à ce mécanisme en excluant le futur des juifs en dehors de l’Europe, à la faveur d’un Etat-nation séparé. Pour Bouteldja, le sionisme de Sartre est le symbole à la fois du refus de la gauche blanche d’abandonner l’État-nation, mais aussi de la récupération obstinée de l’idée d’une innocence européenne.

Par opposition, le contemporain de Sartre est également évoqué, le poète blanc spectateur de la dégénérescence Parisienne, Jean Genet. Genet est resté profondément indifférent aux défaites devenues routinières de la France – à Paris, en Algérie, en Indochine – et profondément conscient que «tout indigène qui se dresse contre l’homme blanc lui offre en même temps la possibilité de se sauver lui-même. » Et c’est à ce carrefour de confrontation et de lutte, argumente Bouteldja, que l’amour révolutionnaire devient possible. Citant le commentaire de C. L. R. James, « Ce sont mes ancêtres, ce sont mes gens. Ils sont les vôtres aussi si vous le voulez », elle nous dit : « James vous offre [les Européens blancs] le souvenir de ses ancêtres noirs qui se sont élevés contre vous et qui, en le libérant, vous ont libéré. En substance, James dit, changez le Panthéon. » Il est déstabilisant de lire ces mots après les récents événements de Charlottesville, où le retrait d’une statue – donc un effort pour changer le panthéon américain – a entraîné la mobilisation d’une coalition meurtrière de nationalistes blancs et de néo-fascistes. L’amour révolutionnaire a un prix, et le prix de la trahison de la blanchité peut être trop lourd à porter pour certains.

La mention de Genet par Bouteldja inclue des références à sa correspondance globale de lettres anticoloniales. C’est Genet qui a écrit l’introduction de Soledad Brother (1970), les écrits recueillis en prison par le marxiste américain noir et militant George Jackson; un an plus tard, après que des gardes l’aient assassiné, des copies manuscrites de poésie palestinienne ont été trouvées dans sa cellule. Le livre de Bouteldja se positionne au sein de ce réseau international de textes. D’ailleurs, sa traduction en anglais (avec une nouvelle préface de Cornel West) constitue elle-même une nouvelle pierre à l’édifice de ce réseau. La mobilisation de Bouteldja des ancêtres noirs américains et francophones souligne les continuités entre le racisme américain et le colonialisme français. Richard Wright l’avait aussi amorcé quand il intitula son élégie militante à la communauté américaine noire « Native Son » [Un enfant du pays] (1940), évoquant ainsi l’homme noir urbain appauvri, tout comme l’indigène de l’Amérique.

Pour sa part, Bouteldja est une enfant du pays, de la France. S’appuyant sur l’écriture politique et sur l’agitation qui a marqué son entrée dans les médias français lors des débats sur le port du voile, Bouteldja formule une critique percutante du féminisme blanc. La femme indigène, explique-t-elle, est prise au piège entre un patriarcat blanc qui veut la sauver de sa famille perçue comme primitive pour consommer son corps, et un patriarcat indigène qui lui fait porter le poids de l’émasculation subie par les hommes indigènes. L’homme blanc conçoit l’homme indigène de la même manière qu’il conçoit la femme – passive et docile. Quand l’homme indigène se révolte, perturbant ainsi les suppositions paternalistes de l’homme blanc, sa virilité inattendue choque et dérange ; elle doit alors être policée, castrée. Cette dynamique équivaut à des jeux Olympiques de virilité entre hommes blancs et indigènes ; en résulte une homophobie misogyne qui prend pour cible à la fois les femmes indigènes et les hommes homosexuels (la lesbienne indigène est largement absente de l’analyse de Bouteldja). Le langage de la castration mobilisé par Bouteldja met au jour le fait que la masculinité phallique de l’homme occidental est aussi prise comme modèle – par défaut – par les hommes indigènes. Pour autant, cette virilité réactionnaire parmi les populations indigènes n’est pas inévitable, et l’expression des identités sexuelles n’a pas besoin d’être stigmatisée pour combattre l’impérialisme. D’ailleurs, le recours par les sionistes à la figure du juif viril et musclé montre que la virilité réactionnaire de l’opprimé a des conséquences désastreuses pour nous tous.

Bouteldja critique également le féminisme indigène romantique, qui analyse la violence masculine sous une forme abstraite, plutôt que de la contextualiser dans le système du patriarcat occidental qui a envahi les pays du Sud. Le féminisme est un luxe, écrit-elle, le luxe de celles qui sont assez blanches et assez européennes et assez chrétiennes pour pouvoir penser leur condition féminine de manière isolée, au centre de leur subjectivité. La seule forme de féminisme responsable impliquerait une alliance communautaire, dans un compromis entre la résistance indigène au féminisme, et une perception de la violence occidentale à laquelle font face tant les hommes que les femmes indigènes.

Une telle position peut sembler quelque peu dépassée, nous ramenant aux conceptions patriarcales des mouvements de droits civiques du milieu du siècle qui subordonnait la double oppression des femmes noires aux préoccupations des dirigeants masculins noirs. Bouteldja cite Assata Shakur de l’Armée de libération noire – «Nous ne pourrons jamais être libres alors que nos hommes sont opprimés» – mais oublie étrangement de mentionner la suite : «Mais il est impératif pour notre lutte que nous construisions un puissant mouvement des femmes noires. ». La citation complète révèle le genre de féminisme décolonial auquel aspire Bouteldja, conduit par une allégeance communautaire, mais sans pour autant s’y arrêter.

Le livre, peut-être involontairement, nous montre qu’un tel féminisme décolonial reste encore loin à l’horizon. L’avant-dernier chapitre fait allégeance à la communauté politique des indigènes en général (on ne sait pas pourquoi Bouteldja ne parle pas spécifiquement aux hommes indigènes, en leur permettant de se fondre dans une norme sans genre spécifique). Le chapitre décrit avec puissance le malaise postcolonial des immigrés de la République française, pris au piège de ce que Frantz Fanon appelait le manichéisme du colonisateur – ils doivent soit devenir français, soit remplir leur rôle pré-pensé de primitifs. Mais ce choix est une ruse: la France n’est pas un melting-pot mais un sable mouvant. En s’intégrant dans la blanchité, l’immigrant postcolonial devient complice de l’impérialisme métropolitain. Comme l’écrit courageusement Bouteldja: « Pourquoi est-ce que j’écris ce livre? Parce que je ne suis pas innocente. J’habite en France. Je vis en occident. Je suis blanche.» C’est dans cette reconnaissance de l’échec de l’intégration qu’une force politique décoloniale commence.

Entre ses remarques destinées aux «Blancs» et celles formulées aux femmes et aux hommes indigènes, Bouteldja s’adresse aussi directement à «Vous, les Juifs». Il est ici évoqué la loi coloniale et la structure sociale en Algérie française, avec les maîtres blancs libres au sommet, les indigènes colonisés à l’autre extrémité, et les juifs algériens (indigènes) au milieu, en tant que tampon privilégié. Mais l’analyse de Bouteldja des Blancs, des Juifs et des peuples indigènes- catégories sociales et politiques qui, selon elle, sont le «produit de l’histoire moderne» – présente un manquement problématique. La blanchité et l’indigénéité sont sans aucun doute, dans leur constitution même, des catégories qui émergent d’une configuration sociale et politique spécifique de pouvoir et de souveraineté. Les juifs ont aussi fait partie de ces configurations coloniales à des moments clés : ils ont été expulsés des colonies françaises en 1685, ils ont obtenu la citoyenneté dans les départements du nord de l’Algérie française en 1870, ont été accusés de trahison et de souillure de la nation française pendant la « belle époque », et ainsi de suite. Mais tout comme Bouteldja cite l’affirmation d’Abdelkebir Khatibi selon laquelle «l’essence arabe précède l’existence d’Israël», l’essence juive précède aussi le colonialisme français. Cette réalité risque d’être oubliée lorsque les «Juifs» sont placés uniquement entre les catégories coloniales de «Blancs» et d’« Indigènes ».

Si Bouteldja s’appuie parfois trop sur cette configuration, son propos polémique bouleverse aussi les divisions sur lesquelles reposent ces catégories. Quand elle regarde les Juifs, « elle nous voit [les indigènes] » – tous deux sont attirés et exclus de la blanchité, tous deux sont diabolisés et disciplinés en Europe, tous deux sont dépossédés l’un de l’autre, mais sont pourtant familiers. Bouteldja décrit fabuleusement les Juifs comme «d’une part, les dhimmis de la République pour satisfaire les besoins internes de l’Etat-nation, et d’autre part, des tirailleurs sénégalais pour satisfaire les besoins de l’impérialisme occidental». Sa phrase «dhimmis de la République» dépeint la France parée de son pinceau orientaliste – prémoderne, religieux, oppressif – et suggère ainsi que, malgré leur prétendue émancipation, le rôle fonctionnel des Juifs en Europe n’a pas changé. Les Juifs sont transformés en «tirailleurs sénégalais», les colonisateurs colonisés à qui l’on sous-traite la perpétuation de la violence impériale. Contrairement à l’offre d’amour proposée aux Blancs, pour laquelle ils devront payer le prix de la révolution, l’offre faite aux Juifs est l’amour de soi – un amour qui rejette l’instrumentalisation israélienne des victimes juives des nazis, la dhimmitude d’un Occident chrétien paternaliste, et la hiérarchie débilitante créée entre les Juifs européens, d’orient, les laïques et les religieux.

La vision de Bouteldja est donc remarquablement inclusive. La lutte, affirme-t-elle, ne se fera pas contre, mais aux côtés des enfants des Harki, ces Algériens indigènes qui ont servi dans l’armée française pendant la guerre d’indépendance du pays. Bouteldja propose cette affiliation tant à la figure des dhimmis que des tirailleurs sénégalais pour les juifs sionistes, dont leurs enfants se doivent de rejoindre le mouvement décolonial. La classe ouvrière blanche elle aussi doit s’engager, non pas par humanisme romantique, ni par un universalisme daltonien, mais parce que les indigènes ont besoin d’anticiper et de combattre les fantasmes réactionnaires du nationalisme et du racisme qui accompagneront inévitablement le développement d’une force décoloniale. Enfin, les indigènes doivent aider les blancs antiracistes et anti-impérialistes qui cherchent de l’aide pour noyer l’homme blanc ancré dans leur subjectivité. Cet équilibre sophistiqué entre autonomie et convergence, qui priorise les revendications des indigènes tout en préconisant l’engagement politique des communautés blanches est une immense promesse aussi pour la gauche américaine, qui est prise entre une approche politique par la classe, et par une caricature d’intersectionnalité, obsédée par la question de l’identité.

Bouteldja termine par une vibrante critique de la laïcité française, en pleine collusion avec le racisme d’État et avec la figure de l’homme blanc désenchanté, venant remplacer Dieu. Elle souligne la promesse ambivalente que l’on trouve dans les traditionnelles approches non laïques de maîtriser un soi hédoniste et consumériste, lequel est débridé dans la culture occidentale. Rappelant le problème que les Juifs posaient à l’Europe des Lumières, Bouteldja reconnaît habilement que, pour les Français blancs éclairés, leurs compatriotes musulmans restent une énigme: malgré l’offre généreuse de rationalité, de démocratie libérale et de modernité, ils s’accrochent toujours aux traditions et à une loi islamique pensée comme prémoderne. En conséquence, ils représentent une menace, car ils « savent quelque chose qui échappe à la Raison ».

Des lecteurs laïques pourront tortiller devant ces propos francs de Bouteldja sur Dieu et sur le potentiel de radicalité dans la soumission devant l’Unique. Mais une telle réaction ne ferait que révéler leur propre soumission à l’hégémonie de la laïcité, avec sa racialisation dédaigneuse du religieux. Les théologies de libération – utopies de libération, comme les appelle Bouteldja – élaborent des connaissances subalternes qui non seulement critiquent l’homme blanc désenchanté et sa violence concomitante, mais offrent aussi à tous ceux du Nord Global – blancs, juifs et indigènes – des outils pour imaginer des futurs alternatifs.

« Les blancs, les juifs et nous » est un texte stimulant, qui provoque tout autant qu’il console et illumine. Mais afin de construire une puissante coalition décoloniale, aspirant à la libération collective, nous devrons avoir la patience d’écouter, la ténacité de contester, et l’humilité d’apprendre du travail de cette femme colonisée.

Ben Ratskoff est un écrivain et intellectuel basé à Los Angeles. Il est le fondateur et le rédacteur en chef des nouveaux Protocoles trimestriels juifs.

Traduction Caro Moop pour Bruxelles Panthères

Liberation Utopias: Houria Bouteldja on Feminism, Anti-Semitism, and the Politics of Decolonization

APRIL 5, 2018

IN MAY 1943, black Surrealist writer and activist Suzanne Césaire made a request for a paper ration from the wartime Vichy government administering Martinique. She needed the paper to print the next issue of Tropiques, a journal devoted to the intersection of Surrealism and anticolonial politics in the Caribbean. The government denied her request; in a dizzying display of doublespeak, the Nazi-collaborationist regime claimed that Césaire’s journal was too racist and sectarian in its brazen engagement with blackness and its literary revolt against French civilization. It is both troubling and illuminating to find a nearly identical discourse surrounding the recent publication of Houria Bouteldja’s Whites, Jews, and Us: Toward a Politics of Revolutionary Love. When the book appeared in France in 2016, a veritable lynching ensued in the media. The uniquely French estate of public intellectuals, both right and left, leaped to discipline this Arab woman who had dared to demystify the fairy tales France tells about itself. Ugly epithets were bandied about: Bouteldja was a racist anti-racist! a neo-Nazi! a homophobe! Not much has changed since Césaire requested the paper ration in Martinique. The Republic doth protest too much.

Bouteldja’s short manifesto continues the tradition of Césaire’s own Surrealist polemic and, most obviously, her husband Aimé Césaire’s groundbreaking Discourse on Colonialism (1950). Artfully and sensitively rendered into English by Rachel Valinsky, Whites, Jews, and Us offers a passionate and poetic manifesto that takes aim at the imperial metropole and its myths of innocence. The book is shot through with a bracing optimism, making a magnificent appeal for a metropolitan decolonial movement as a political force for liberation. Bouteldja tackles issues of Eurocentrism, imperialism, and globalization and experiments with a form of political organizing that, in the words of her comrade Sadri Khiari, attempts “to think unity and division together and accept convergence and antagonism as paradoxical paths” to liberation.

The first chapter identifies a contradiction that will frame the book’s address to whites, Jews, and indigenous people: Jean-Paul Sartre’s unrepentant Zionism. On the one hand, Sartre defended anticolonial militancy in Algeria and the Middle East; on the other hand, he supported the formation of a Jewish nation-state in Palestine. Bouteldja contends that Sartre’s simultaneous embrace of anticolonialism and Zionism was due, essentially, to his whiteness. Whiteness, in short, marked the insufficiency of his politics. In a provocative passage, Bouteldja writes: “He who declared ‘It is the anti-Semite who makes the Jew’ now prolonged the anti-Semitic project in its Zionist form and participated in the construction of the greatest prison for Jews. In a rush to bury Auschwitz and to save the white man’s soul, he dug the Jew’s grave.” In other words, Sartre both comprehended anti-Semitism as a European mechanism of exclusion and participated in this very mechanism by excluding Jewish futures from Europe in favor of a separate nation-state. For Bouteldja, Sartre’s Zionism becomes symbolic of both the white left’s refusal to abandon the nation-state and its dogged recuperation of European innocence.

Sartre’s foil in the book is the white bard of Parisian degeneracy, Jean Genet. Genet remained both profoundly indifferent to France’s routine defeats — in Paris, in Algeria, in Indochina — and keenly aware that “any indigenous person who rises up against the white man grants him, in the same movement, the chance to save himself.” It is at this crossroads of confrontation and struggle, Bouteldja argues, that revolutionary love becomes possible. Citing C. L. R. James’s comment, “These are my ancestors, these are my people. They are yours too if you want them,” she says: “James offers you [white Europeans] the memory of his negro ancestors who rose against you and who, by freeing him, freed you. In essence, James says, change the Pantheon.” It is haunting to read these words after the recent events in Charlottesville, where the removal of a statue — an effort to change the American pantheon — mobilized a deadly coalition of white nationalists and neo-fascists. Revolutionary love comes at a cost, and the price of betraying whiteness may be too steep for some to bear.

Bouteldja’s inclusion of Genet invokes a global itinerary of anticolonial letters. It was Genet who wrote the introduction to Soledad Brother (1970), the collected prison writings of black American Marxist and activist George Jackson; a year later, after guards murdered him, handwritten copies of Palestinian poetry were found in his cell. Bouteldja situates her book within this transnational network of texts. Indeed, its translation into English (with a new foreword by Cornel West) itself represents an important new node in this network. Bouteldja’s mobilization of black American and Francophone ancestors underscores the continuities between American racism and French colonialism. Richard Wright had suggested as much when he titled his militant elegy to black American manhood Native Son (1940), thus evoking the impoverished urban black man as America’s indigène.

For her part, Bouteldja is France’s native daughter. Building upon the political writing and agitation that marked her entry into French media during the hijab debates, Bouteldja mounts a blistering critique of white feminism. The indigenous woman, she argues, is trapped between a white patriarchy that wants to save her from her primitive family only to consume her body and an indigenous patriarchy that makes her bear the brunt of the indigenous man’s emasculation. The white man imagines the indigenous man as his feminine foil — passive and docile. When the indigenous man revolts, confusing the white man’s paternalistic assumptions, his unexpected virility shocks and disturbs — and must be policed, castrated.

This dynamic amounts to a game of virility Olympics between white and indigenous men, deploying a misogynous homophobia that targets both indigenous women and queer males (the indigenous lesbian is largely absent from Bouteldja’s analysis). Bouteldja’s language of castration reinscribes the phallic masculinity of Western man as the default model for indigenous men as well. Reactionary virility among indigenous populations, however, is not inevitable, and indigenous queerness need not be marginalized in order to fight imperialism. The deployment by Zionists of the figure of the virile, muscular Jew shows that the oppressed’s reactionary virility has dire consequences for us all.

Bouteldja also critiques the romantic, indigenous feminism that indicts masculine violence in the abstract, rather than locating it within the system of Western patriarchy that has penetrated the Global South. Feminism is a luxury, she writes, the luxury of those white enough and European enough and Christian enough to see their womanhood isolated at the center of their subjectivity. The only responsible form of feminism involves communitarian allegiance, a compromise between indigenous resistance to feminism and an understanding of the Western violence faced by indigenous men and women alike.

Such a position can feel somewhat dated, recalling the patriarchal politics of midcentury civil rights movements that subordinated the double oppression faced by black women to the concerns of the black male leadership. Black women have long addressed and critiqued their erasure by both white feminists and black men. Bouteldja cites Assata Shakur of the Black Liberation Army — “We can never be free while our men are oppressed” — but strangely leaves out her subsequent qualification: “But it is imperative to our struggle that we build a strong black women’s movement.” The full quotation reveals the kind of decolonial feminism to which Bouteldja aspires, routed through communitarian allegiance but not stopping there.

The book, perhaps in spite of itself, signals that such a decolonial feminism still remains far on the horizon. The penultimate chapter embraces an allegiance to the political community of the indigenous in general (it is unclear why Bouteldja does not specifically speak to indigenous men, instead permitting them to fade into a genderless norm). The chapter powerfully describes the postcolonial malaise of the French Republic’s immigrants, trapped in what Frantz Fanon termed the Manicheanism of the colonizer — they must either become French or fulfill their preordained role as primitive native. But this choice is a ruse: France is not a melting pot but a quicksand. By integrating into whiteness, the postcolonial immigrant becomes complicit with metropolitan imperialism. As Bouteldja bravely remarks: “Why am I writing this book? Because I am not innocent. I live in France. I live in the West. I am white.” It is in this acknowledgment of integration’s failure that a decolonial political force begins.

Between her comments posed to “White People” and those addressed to indigenous women and men, Bouteldja directly engages “You, the Jews.” Her title evokes colonial law and social structure in French Algeria, with the free white masters on top, the colonized indigenous at the bottom, and the (indigenous) Algerian Jews in the middle, as a privileged buffer. But Bouteldja’s deployment of whites, Jews, and indigenous peoples — social and political categories that, she claims, are the “product of modern history” — involves an uncomfortable erasure. Whiteness and indigeneity are certainly, in their very constitution, categories that emerge from a specific social and political configuration of power and sovereignty. And Jews were definitely thrust into this colonial configuration at pivotal moments: they were expelled from the French colonies in 1685, granted citizenship in the northern departments of French Algeria in 1870, accused of treason to and defilement of the French nation during the belle époque, and so on. But just as Bouteldja cites Abdelkebir Khatibi’s assertion that “Arab essence precedes the existence of Israel,” so too Jewish essence precedes French colonialism. This reality risks being forgotten when “Jews” are merely placed between the colonial categories “Whites” and “Indigenous.”

If Bouteldja relies at times too heavily on this configuration, her polemic also subverts the divisions that sustain it. When she looks at Jews, “she sees us [indigenous]” — both are attracted to and excluded from whiteness, both are demonized and disciplined within Europe, both are dispossessed from one another and yet still familiar. Bouteldja fabulously describes the Jews as “on the one hand, dhimmis of the Republic to satisfy the internal needs of the nation state, and on the other, Senegalese riflemen to satisfy the needs of Western imperialism.” Her phrase “dhimmis of the Republic” paints France with its own Orientalist brush — as pre-modern, religious, oppressive — and suggests that, despite their so-called emancipation, the functional role of Jews in Europe has not changed. At the same time, Jews are made into “Senegalese riflemen,” the colonized colonizers to whom the perpetuation of imperial violence is outsourced. Unlike the offer of love made to whites, for which they must pay the price of revolution, the offer to Jews is self-love — one that rejects Israel’s instrumentalization of the Nazis’ Jewish victims, the dhimmitude of a paternalistic Christian West, and the debilitating, transplanted hierarchy between European and Eastern, secular and religious Jews.

Bouteldja’s vision is thus remarkably inclusive. The struggle, she asserts, will not be against but beside the children of the Harki, those indigenous Algerians who served in the French Army during the country’s war of independence. Bouteldja thus implies affiliation as well with the dhimmis of the Republic and the Senegalese riflemen — with, in essence, Jewish Zionists — whose children too must join the decolonial camp. The white working class must also be engaged, not out of a romantic humanism or color-blind universalism but because the indigenous need to anticipate and combat the reactionary phantasms of nationalism and racism that will inevitably accompany the development of a decolonial force. And finally, the indigenous must assist the anti-racist and anti-imperialist whites who are seeking help in annihilating the white man at the center of their being. This sophisticated balance between autonomy and convergence, which prioritizes the claims of the indigenous while advocating the political organization of white communities, holds tremendous promise for an American left caught between a class-based politics and an identity-obsessed caricature of intersectionality.

Bouteldja ends with a stirring critique of French secularism (laïcité), its collusion with state racism, and the disenchanted white man with which it replaces God. She outlines the ambivalent promise found in non-secular traditions for subduing the hedonistic, consumerist self unleashed by Western culture. In an uncanny reminder of the problem Jews posed to Enlightenment Europe, Bouteldja deftly recognizes that, to enlightened white Frenchmen, their Muslim countrymen are an enigma: despite the generous offer of rationality, liberal democracy, and modernity, they still cling to pre-modern Islamic law and tradition. As a result, they are also a threat, because they “know something that escapes white Reason.”

Secular readers may squirm at Bouteldja’s frank discussion of God and the radical potential of submission before the One. Such a response would only reveal their own submission to the hegemony of the secular, with its dismissive racializing of the religious. Theologies of liberation — liberation utopias, as Bouteldja calls them — elaborate subaltern knowledge that not only critiques the disenchanted white man and his attendant violence, but also offers all those in the Global North — whites, Jews, and indigenous — tools for imagining alternative futures. Whites, Jews, and Us is a challenging text that provokes just as much as it consoles and illuminates. But in order to build a forceful decolonizing coalition that aspires to collective liberation, we must have the patience to listen to, the tenacity to challenge, and the humility to learn from the work of this colonized woman.

¤